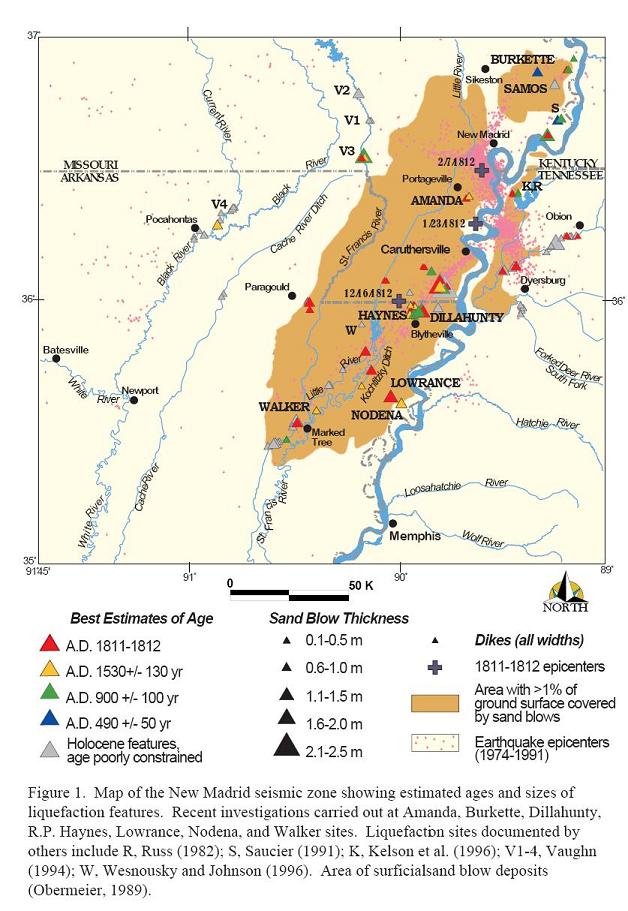

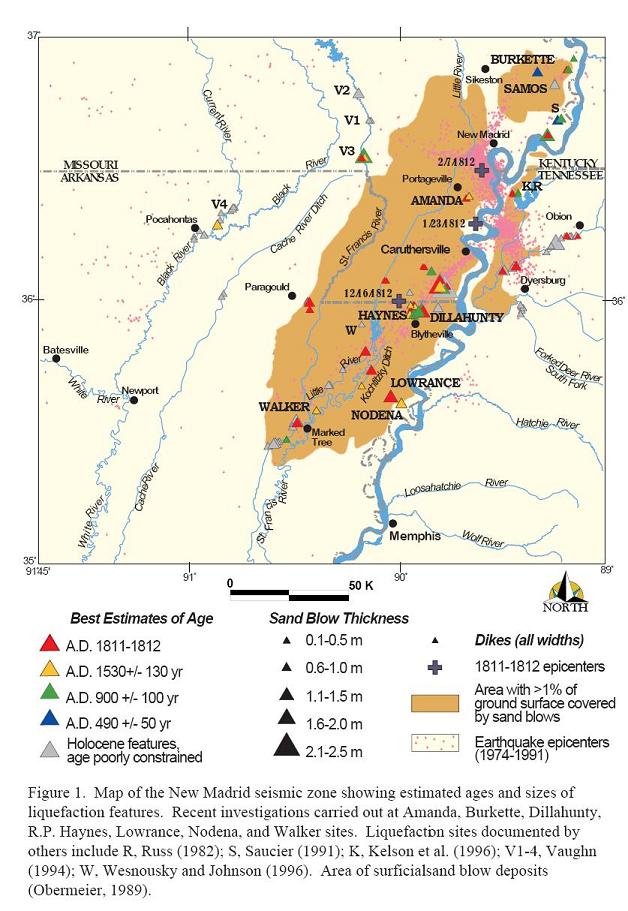

Liquefaction features documented at 112 sites indicate that very large earthquakes have struck the New Madrid region in

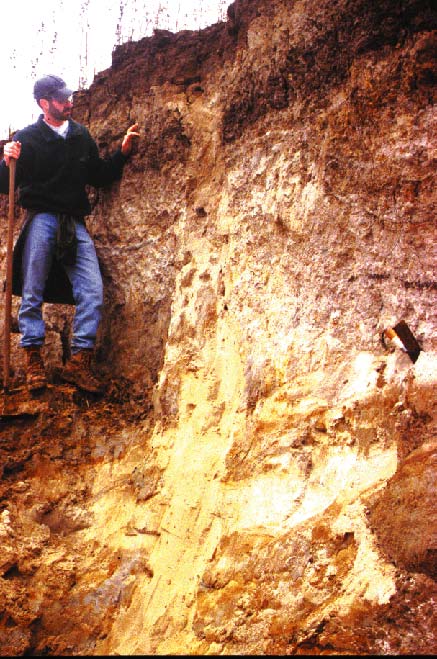

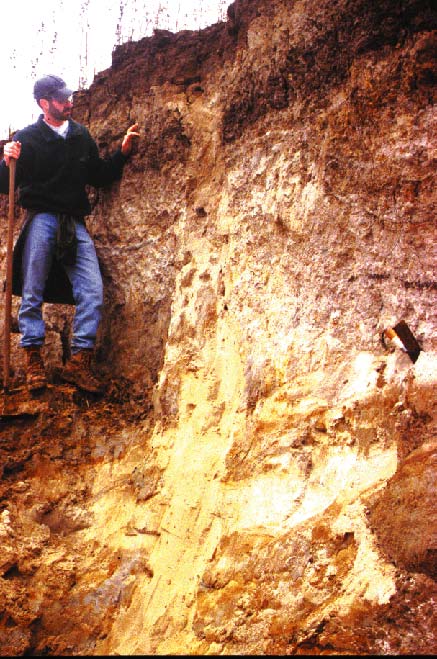

A large sand blow exposed along the Current River in the Western Lowlands is suggestive of a large earthquake about A.D. 1380. It may be related to others on the St. Francis River.

The area and size distributions of related liquefaction features suggest that the A.D. 900 event was quite similar to the 1811-1812 earthquake sequence. The A.D. 900 event induced liquefaction over a large area and may have been of M > 7.4. If the features were formed as a result of a single earthquake, the areal and size distributions of liquefaction features suggest that the earthquake may have been centered near Blytheville, Arkansas.

Less is known about the A.D. 1450-1470 event but it, too, may have been very large. ...strong evidence that this event occurred during the Late Mississippian cultural period (A.D. 1400-1670). The areal and size distribution of liquefaction features suggest that the earthquake may have been centered near Blytheville, Arkansas, and been of M > 7.2

It appears that very large earthquakes have occurred in the NMSZ every 200 to 800 yr during the past 1200 yr.

In addition, we have evidence for at least three earlier events between 4040 B.C. and A.D. 780. Prehistoric liquefaction features found as far away as southern Illinois may be related to New Madrid seismicity.

from Tuttle, Schweig 1997

http://erp-web.er.usgs.gov/reports/abstract/1997/cu/g3082.htm

A geologic fault is defined as a break in earth materials (rocks or soil) with relative displacement between both sides.

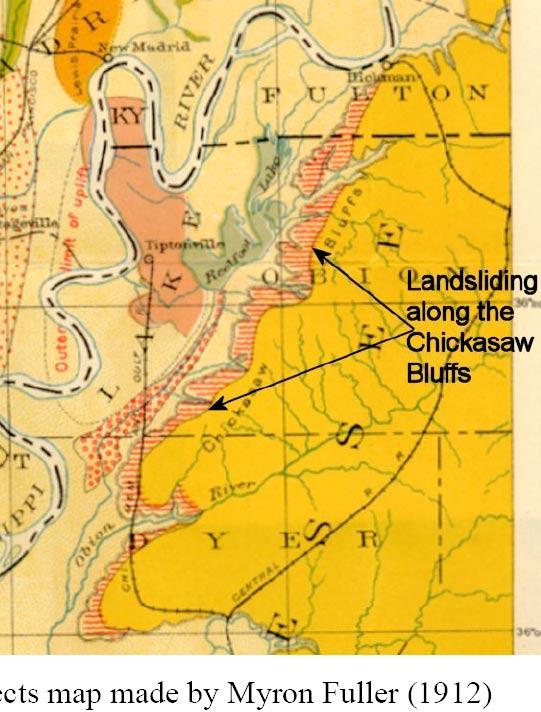

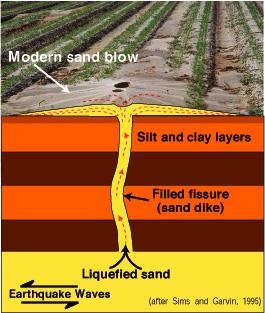

Primary faults cause earthquakes. Secondary faults are caused by earthquakes. There are numerous secondary faults in the NMSZ that can be seen, but no visible primary faults.

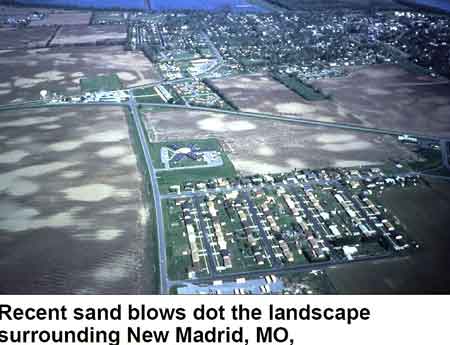

There is a lineament (now called fault) through the Bootheel of Missouri visible by high resolution satellite imagery (Schweig & Jibson, 1989). This lineament is almost a perfect, straight line dividing differences in surface soils and topography from four miles west of Blytheville to nine miles west of New Madrid. Some of the largest seismic sand boils are along this line.

"Damages and Losses from Future Earthquakes" by David M. Stewart, Southeast Missouri State University, 1993, Care Publications. ISBN 0934426538

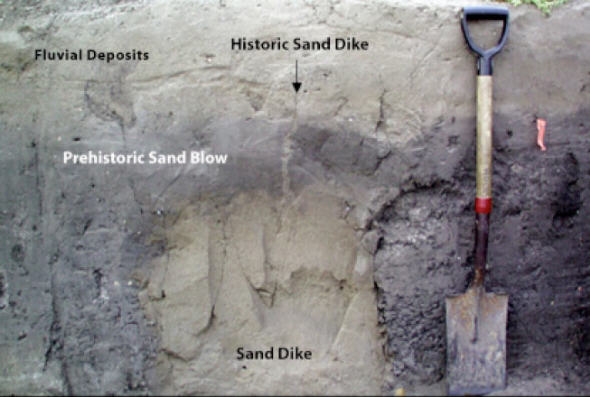

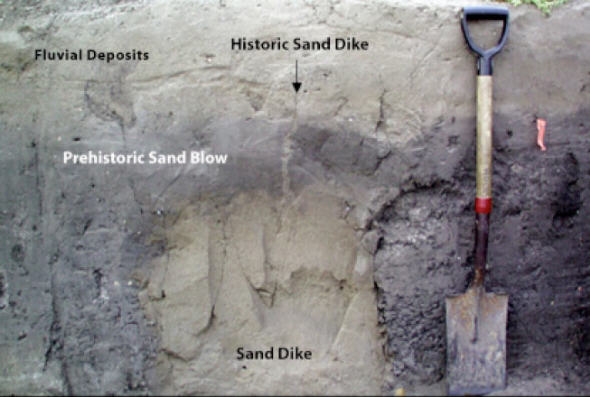

Tuttle and USGS geologists found that recently excavated sandblasts predated the famous New Madrid quake by hundreds of years. Using radioactive carbon dating techniques, they estimated the ages of hickory nuts, corn kernels or other organic material they found in sediment above and below the blasts.

Tuttle's most recent results, published in 2002, suggest that other massive New Madrid earthquakes happened about A.D. 900 and 1450. Some preliminary evidence points to another quake about A.D. 300, she said. If the pattern holds--one huge quake every 500 or 600 years--the New Madrid zone would see another such event within the next few centuries.

The fault system responsible for New Madrid seismicity has generated temporally clustered very large earthquakes in A.D. 900 ± 100 years and A.D. 1450 ± 150 years as well as in 1811–1812. Given the uncertainties in dating liquefaction features, the time between the past three New Madrid events may be as short as 200 years and as long as 800 years, with an average of 500 years.

... It appears that fault rupture was complex and that the central branch of the seismic zone produced very large earthquakes during the A.D. 900 and A.D. 1450 events as well as in 1811–1812. On the basis of a minimum recurrence rate of 200 years, we are now entering the period during which the next 1811–1812-type event could occur.

Guccione and others, GSA Bulletin; March 2005; v. 117; no. 3-4; p. 319-333; DOI: 10.1130/B25435.1

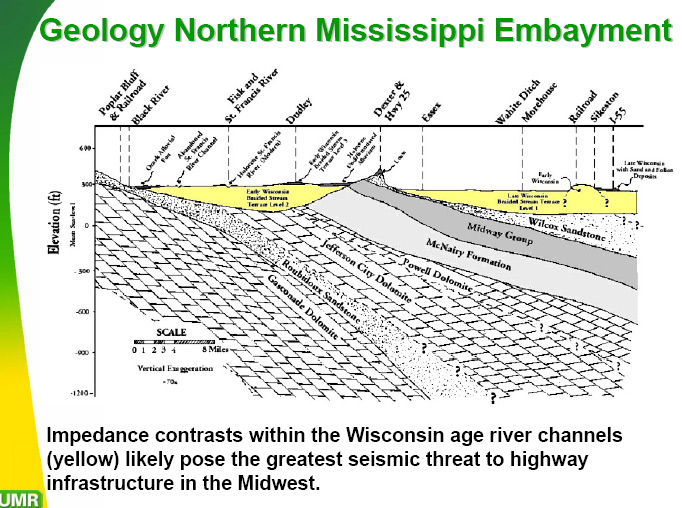

The sands, silts, and clays are an average 477 meters deep at New Madrid, deepening to 987 meters near Memphis. The numbers are from a study by Roy Van Arsdale and Robin TenBrink.

http://bssa.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/90/2/345

5,000 and 7,000 years ago - "Daytona Beach" sandblow

now growing cotton on white sand SW of Memphis.

At the Burkett archeological site in southeastern Missouri [near Charleston], there is evidence for at least six earthquakes that induced liquefaction and related ground failures during the past 4,500 yr. The four earliest earthquakes occurred in 2350 B.C. ± 200 yr and may have been part of an earthquake sequence occurring over a period of weeks to months. Sand blows and related sand dikes that formed as a result of these earthquakes served as the foundation on which a Late Archaic and Woodland cultural mound was built. The fifth earthquake occurred in A.D. 300 ± 200 yr towards the end of the Middle Woodland period. The sixth and latest earthquake occurred after A.D. 1670. Given that it produced small sand blows and liquefaction-related ground failures not far from the site, the 1895 Charleston, Missouri, earthquake was more likely the cause of the small historic sand dikes at Burkett than the 1811-1812 New Madrid earthquakes.

The 2350 B.C. and A.D. 300 earthquakes are interpreted as 1811-1812-type or New Madrid events. This interpretation is based on the relatively large size of the prehistoric liquefaction features at Burkett, the close timing of the four earthquakes in 2350 B.C., and the likelihood that the 2350 B.C. and A.D. 300 earthquakes also induced liquefaction at other sites in northeastern Arkansas and southeastern Missouri.

from http://erp-web.er.usgs.gov/reports/abstract/2001/cu/01hqgr0164.pdf

What is liquefaction?

Below: Cross-section of a sand blow in New Madrid area, likely in Wolf River in Collierville, SE of Memphis. USGS photo.

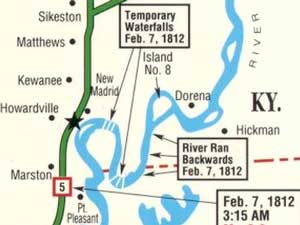

Deformation, liquefaction area of New Madrid region

Below: Map of larger sand boils

At three sites near Blytheville, Arkansas, in the central part of the New Madrid seismic zone, one sand-blow crater formed between A.D. 800 and 1400, two sand-blow deposits formed between A.D. 800 and 1670, and three, possibly four, sand dikes formed since 4035 B.C. - source

In Jan., 2001, a 7.9 earthquake struck Bhuj, in extreme western India. Earthquake investigators say it has similarities to the worst-case New Madrid scenario.

|

Memphis' city and county government in 1991 built a 32-story pyramid on its riverfront. It could

hold 20,000 spectators, is the size of six football fields, is slightly taller

than the Statue of Liberty, and held great promise as sports arena/convention

center. In 1992 the city started considering earthquake construction standards.

The pyramid sits smack dab on a Mississippi River sandbar. Guess what could

happen to 20,000 spectators in the event of a major quake. It is being remodeled

into a huge sporting goods store.

Memphis' city and county government in 1991 built a 32-story pyramid on its riverfront. It could

hold 20,000 spectators, is the size of six football fields, is slightly taller

than the Statue of Liberty, and held great promise as sports arena/convention

center. In 1992 the city started considering earthquake construction standards.

The pyramid sits smack dab on a Mississippi River sandbar. Guess what could

happen to 20,000 spectators in the event of a major quake. It is being remodeled

into a huge sporting goods store.